Best Ever

Progressive Rock Album?

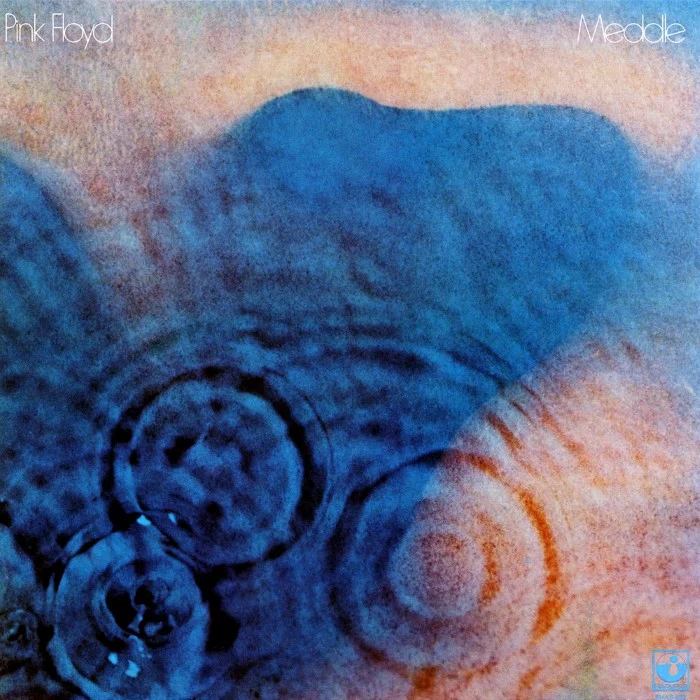

Meddle

"Before the concept albums consumed them, Pink Floyd made their most texturally adventurous record—a 23-minute song about absolutely nothing that somehow contains everything."

There’s a moment six minutes into “Echoes” where the song simply stops being a song. The chord progression evaporates. Seagulls emerge—or whales, or the screaming void between galaxies. Rick Wright’s organ becomes sonar pinging off the walls of some underwater cathedral. For the next several minutes, Pink Floyd doesn’t play music so much as generate atmosphere, the way a cave generates stalactites: slowly, minerally, through processes that have nothing to do with human intention.

This is the Pink Floyd that gets lost in the discourse. We talk endlessly about The Dark Side of the Moon’s conceptual unity, Wish You Were Here’s elegiac grief, The Wall’s theatrical bombast. But Meddle, released in October 1971, represents something rarer and stranger: the last moment when Pink Floyd operated purely on sonic instinct, before Roger Waters discovered he had Very Important Things to say about capitalism and alienation and his father dying at Anzio.

Meddle has no concept. It barely has lyrics. What it has is texture—layer upon layer of guitar that sounds like it’s being played through honey, drums that seem to arrive from an adjacent room, keyboards that exist in some uncanny valley between baroque and kosmische. “One of These Days” opens the record with a bassline so distorted it becomes purely percussive, a heartbeat recorded through a stethoscope made of fuzz pedals. Nick Mason’s single whispered line—“One of these days I’m going to cut you into little pieces”—functions less as lyric than as found sound, another texture in the mix.

And then there’s “Fearless”—a song so quietly perfect it tends to get overlooked amid the album’s more obvious ambitions. Built on a fingerpicked acoustic progression that wouldn’t sound out of place on a Nick Drake record, it layers Gilmour’s slide guitar and those eerie, wordless harmonies into something that somehow manages to be both intimate and vast. The Liverpool FC crowd singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone” at the song’s end shouldn’t work—it’s the kind of found-sound experiment that usually screams “art project”—but it does, transforming a folk song into a hymn for collective perseverance.

Richard Linklater understood this. In Everybody Wants Some!!, his 2016 spiritual sequel to Dazed and Confused, there’s a scene where the baseball team’s resident stoner puts “Fearless” on the turntable and the room just… stops. No dialogue. No plot advancement. Just a bunch of college kids in 1980 letting this song wash over them, the camera finding each face as the harmonies build. It’s Linklater at his most generous—trusting that the song will do the work, that we’ll understand why this moment matters without being told. He’s right. “Fearless” earns that kind of attention.

Side one’s sequencing demonstrates perverse confidence: pastoral drift, genuine funk via “Fearless,” a jazz-lounge throwaway in “San Tropez” that sounds like it wandered in from a different session. None of it prepares you for side two, which is simply “Echoes” in its entirety. Twenty-three minutes and thirty-one seconds. One song.

And here’s the thing: it earns every second.

“Echoes” isn’t prog-rock showboating, isn’t the endless noodling that would soon make the genre synonymous with self-indulgence. It’s genuinely architectural, built from a single piano note (Wright playing through a Leslie speaker, creating that distinctive wobbling tone) into something that encompasses call-and-response vocals, David Gilmour’s most lyrical solo work, that terrifying middle section of pure abstraction, and a return to the theme that somehow feels like coming home after a journey you didn’t know you’d taken.

The production, handled by the band themselves, achieves something remarkable: it sounds both absolutely of its moment and weirdly timeless. There’s none of the dated quality that afflicts so much early-’70s rock. When Gilmour’s guitar enters on “Echoes,” it exists in its own pocket of space, neither too forward nor too recessed, simply there in a way that modern recording rarely achieves. Engineer John Leckie, early in a career that would later encompass Radiohead and The Stone Roses, helped capture a band at the exact moment of maximum possibility.

What makes Meddle the best progressive rock album isn’t its technical complexity—Yes was already releasing more virtuosic material, King Crimson more aggressively avant-garde. It’s that Pink Floyd understood prog’s real potential: not showing off, but world-building. Every sound on this record exists in service of creating a space you can inhabit. The seagull noises in “Echoes” aren’t pretentious; they’re logical. Of course that’s what you’d hear in this particular sonic environment. Of course the song would need to pass through abstraction to reach its resolution.

Listen to Meddle on headphones late at night and you’ll understand why people followed this band anywhere—even into the bloated arena-rock wilderness of their later years. For forty-six minutes in 1971, Pink Floyd made an album about nothing that turned out to be about everything: space and time and the strange comfort of getting genuinely lost in sound.

Decide for Yourself:

- The 2016 vinyl remaster restores the album’s remarkable dynamic range—crucial for experiencing how ‘Echoes’ moves from whisper to roar and back again.

- The 2021 Blu-ray features a new mix by Steven Wilson that reveals details buried in the original—you’ll hear guitar parts in ‘Echoes’ you never knew existed.

- The original 1971 UK pressing on Harvest remains the grail for collectors—the pressing quality at EMI’s Hayes plant was exceptional.

By Paco Picopiedra

December 9, 2025